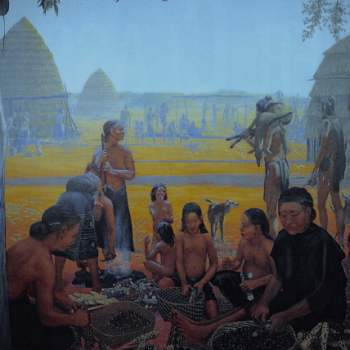

A Story of Salt

The discovery of numerous submerged saltworks in Southern Belize is yielding insights into the Maya’s economic system, the esurvival of their wooden material culture, and ancient climate change.

American Archaeology — Spring 2017

Salt is a substance so ordinary and inexpensive today that its ready supply is often taken for granted. Yet salt is essential: humans need salt to live and also crave it as a flavoring and rely on it as a preservative.

For the ancient Maya residents of Nim Li Punit, Lubaantun, and other inland cities in Belize’s southern lowlands, there was a paucity of nearby sources. So archaeologists assumed they imported their salt from distant flats on the north coast of the Yucatan Peninsula.

But Louisiana State University archaeologist Heather McKillop appears to have disproven that assumption. McKillop has uncovered evidence that the Maya produced salt on a large scale in workshops on Belize’s southern coast and transported it to the cities. McKillop has found pottery vessels that were used to collect salt from evaporated brine as well as the remains of workshops where salt was produced. “Heather McKillop’s contribution, a major one, is that she has enhanced our understanding of the methods the Maya used for exploiting marine resources,” said archaeologist Jaime Awe, the former director of Belize’s Institute of Archaeology and now a professor at Northern Arizona University. “Her research is contributing to the understanding of the complexities of trade before the arrival of the Spanish.”

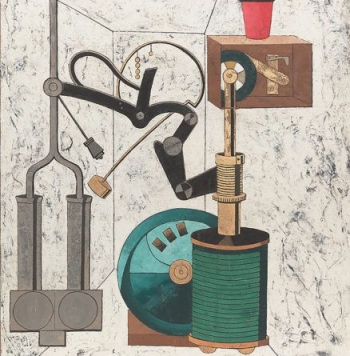

Francis Picabia’s Chameleonic Style

JSTOR DAILY — FEBRUARY 15, 2017

The Museum of Modern Art’s current retrospective of Francis Picabia’s work has been celebrated by critics for shining a spotlight on one of modernism’s most confounding founders. ArtNews called the exhibit “one of the best shows of the year,” and Forbes declared it “exhilarating.”

What strikes most visitors is the exhibit’s sheer variety. Throughout his career, Picabia careened between styles, flipping from Cubism to Dadaism, from abstraction to portraiture. In fact, he rarely stuck with a style for more than a few years. A fiercely independent artist, he ignored movements and shunned trends. “If you want to have clean ideas, change them as often as your shirt,” Picabia advised.

The Road to Prehistory

When archaeologists discovered several ancient Caddo sites during a highway expansion project in Texas, they had to make some difficult decisions about what could be preserved.

American Archaeology — Fall 2016

U.S. Highway 175 emerges from the sprawl of Dallas, shaking off the suburbs as it stretches southeast. Just beyond the city of Athens, this four-lane highway narrows to two lanes. Through Anderson and Cherokee counties it continues up and down rolling hills until it reaches Jacksonville, and terminates at the intersection with U.S. Highway 69.

Southeast of Athens, the highway runs along a low hill. In the sparse shade provided by a few tents, a team of archaeologists scrapes and sifts the soil near the roadway. Some 500 years ago, a small community of Caddo people occupied this hillside. They grew maize and beans, made tools from bone and rock, lives and died, and were buried in this quiet corner of the world. But this hillside is soon to be transformed. U.S. 175 is scheduled to be widened to four lanes and portions of the Caddo sites will be bulldozed and paved. Work is already underway several miles back toward Athens, with crews grading the new roadway with enormous earth-moving equipment.

Monet Employed a Water Lily Duster!

But that’s not the most radical thing about the Impressionist master’s best-known work

Mental_Floss — January/February 2016

As the sun rose over Giverny, France, a gardener paddled a small boat out into Claude Monet’s backyard pond. Then, he began gently submerging lily pads into the water one by one, washing away any dust that had accumulated overnight. Monet watched from the bank, his palette in hand. He was ready to begin the day’s work, but first, as always, he insisted that the lilies be properly dusted.

Monet was captivated by his pond: the distorted reflections on the surface, the swirling weeds below, the way the light played on it all. He hadn’t always paid it so much attention. At first, he said, “I grew [water lilies] without thinking of painting them … then, all of a sudden, I had the revelation of the enchantment of my pond. I took up my palette.”

Publications Include: